Analyzing Writing

Part 1: Conception

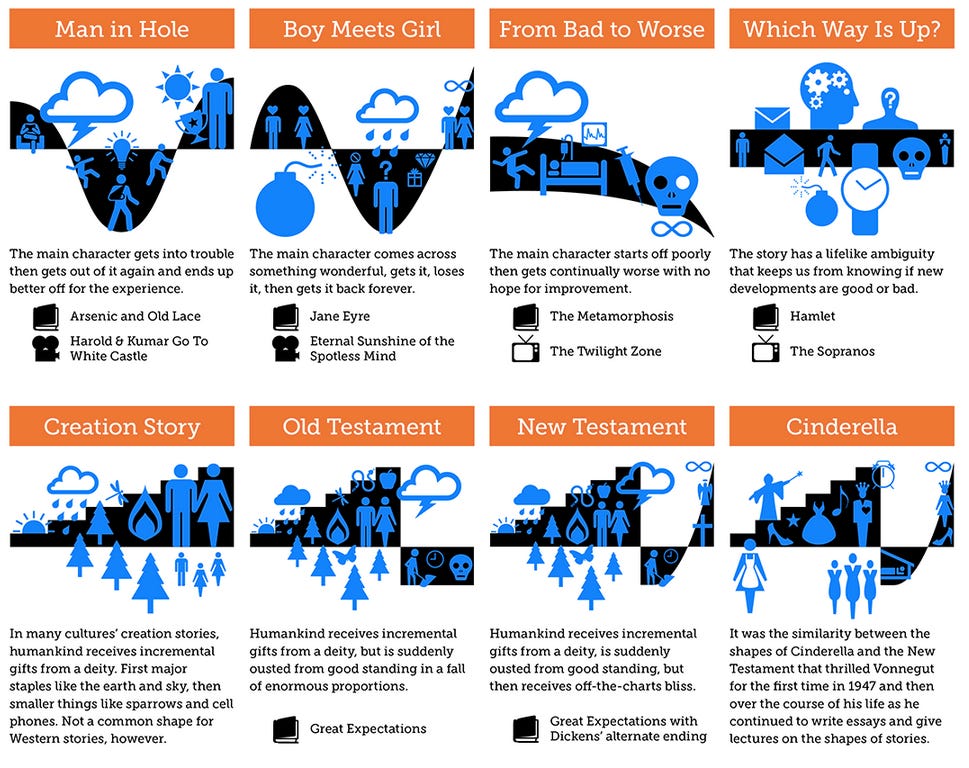

Writing, in itself, is a derivative act. Each piece of media we writers ingest expels itself in one way or another, whether that be a line of dialogue or a particular set piece that intrigues us. There are only so many stories to be told, arcs for characters to go on, or lessons to be taught. Kurt Vonnegut, in his novel A Man Without a Country, illustrates, what he (and I) believe to be the only eight “shapes” or directions a story can go. However, what makes storytelling so long lasting isn’t the ways a story can end, but the way the writers tell it.

Vonnegut’s 8 Shapes of Stories

In particular, when I write I find myself coming up with ideas that partially resemble whatever I had read or watched that had impressed me. This is the first step in my creation process, taking a riveting section from a novel or television show, and adding my own flair, my own characters, my own voice. I also try and think of a theme or message I really relate to and shape the clay from there, adding the water of other pieces to help mold the shape.

I’ve been doing this as a writer for as long as I can remember. My first short story I ever wrote, in 6th grade, come hot off the tails of me reading Harry Potter. I was obsessed with the idea of wizards, but I wasn’t British, so I set the story around a boy in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania finding out he was a secretly famous warlock. Basic, sure. But writing a book based in the city you lived in taken from an already existing story isn’t new. Does Steinbeck and East of Eden ring any bells?

John Green, author of The Fault in Our Stars talks about his process of writing on his personal website. Specifically regarding the conception process, he shares my (and many others’) sentiment about taking a theme or message you find intriguing and expanding upon it, imbuing your own flavor and life. He mentions how he came up with the idea for his first book, Looking for Alaska, because he was intrigued with the concept of grief and how it guides the decisions we make, especially when we’re adolescents.

Max’s Succession, recently ended, falls under this same conceptual process. Jesse Armstrong, the showrunner, remarked in a New Yorker Interview how he was fascinated with the one percent’s disillusionment in his thinking up of the show. This, combined with the state of American politics at the time, mixed with a dash of King Lear (From Bad to Worse on Vonnegut’s chart), ultimately created the multiple-Emmy-award-winning show’s engine.

So my method of thinking isn’t new; it’s as old as writing has been around.

Part 2: The Meat and Potatoes, Part 1

Because of writing’s ever-present place within society, there should be a clear methodology and timeline breaking down the process, with each era of humanity coming into play. While this is true for the end result of novels or screenplays, the same can’t be said for the actual process of sitting down and creating. This means that the act of putting words on page is strangely contemporary; there is a blur between past, present, and future.

Each author or screenwriter walks at their own pace, tells their story at a speed that it needs to be said, or that it comes to them. There are famous stories of writer’s taking years to complete their process of finishing. George R. R. Martin, notably, is over a decade late on delivering his latest book in the Game of Thrones series, and Neil Gaiman recently came to X (formerly Twitter) and stated he wrote the book Coraline at fifty words a night.

In my own writing, I tend to move a little bit quicker than those aforementioned, but am no means churning out pages upon pages. I consider myself a writer in two regards, prose and screenwriting mainly, and despite their formatting differences, my process remains mostly the same.

With screenwriting, it can vary, but it hovers around 3-5 pages a night after an arduous outlining process which involves breaking my movie or pilot down act by act. But, during actual “page writing”, if I write one or two solid scenes, I’m satisfied for the time being (only for me to most likely come with a sword and shield and tear it shreds later). Occasionally, if I’m feeling particularly inspired, I can work up to 7-8, but try to avoid writing much more in a single day, as I don’t find I can get good, solid pages after that. When I write prose, the numbers break down slightly differently. I try and aim for 1,500-2,000 laudable words in a day. Any less, I tend to feel rather glum, but any more, I start to develop a tunnel vision headache and start throwing garbage on the page.

Once in a while, if I’ve gotten something really good, I find what I akin to a runner’s high, a break through in the slog of the initial creative swamp writing a new book or short story brings. In her talk at Columbia, author Zadie Smith calls this feeling the middle-of-the-novel-magical-thinking, where hours flash in the blink of an eye and the world outside of your story melts away — the only thing that remain are you and the page.

This is a very real experience, but what Zadie Smith fails to mention is the post-adrenaline come down, the feeling you have after you get into a car accident where your body shuts down because it was on overdrive. There will never be a better sleep than after falling into the hypnotized trance of inspiration.

The act of writing has been around for so long, it would take a lifetime to even begin compiling a comprehensive list of each person’s individual process for sitting down and writing, then group that into a genre. The written language is assumed to have started at around 3500 BCE at the earliest in Mesopotamia, meaning there is over 5000 years of written word in humanity.

Part 3: The Meat and Potatoes, Part 2

One of the most valuable pieces of writing advice given to me as a student as USC is the 48-minute method. This revolves around the practice of isolating yourself in a quiet, focused room and committing to doing nothing but writing for 48 minutes. I was told to set a timer for myself and as soon as the timer goes off, get up, stretch, and take a break for 12 minutes. Using this method has helped me write my last 2 screenplays and a short story.

During these 12 minutes, I listen to music that puts me deeper in the world of whatever I happen to be writing about. Last year, when I was writing a pilot of a western, during my breaks, I would curate a playlist full of Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, and Loretta Lynn. They keep me grounded in the script, and occasionally, a song of theirs motivates me to write a scene using it as a soundtrack.

Oscar winner Aaron Sorkin, creator of the The West Wing and The Social Network states in his Masterclass that he does the same thing. Although he doesn’t use the 48/12 method, he’ll take long walks or drives to music, and once in a while, a song will come on and he can perfectly picture a scene. Motivated, he’ll speed back home and type it out.

Strangely, a difficult part of the 48 minute method is that no matter where you are in the script or prose, no matter how motivated you are, as soon as the timer sounds, you have to stop what you’re doing. I find that this is actually beneficial when I return from my 12 minute break, because then I’m able to hit the ground running after bundling my energy.

Part 4: The Dreaded Rewrite

Every writer has been told that rewriting is equally as important, if not more, than the actual writing itself. In my experience, rewriting is the most taxing aspect of storytelling. Part of this has to do with the fact that once I finish a first draft, my body reacts like I’ve finished a marathon — exhausted, borderline delirious, and starving. I’ve written a story! Why would I want to change anything?

It only takes a few days of settling down to realize that it’s bad and I would hate for anybody to read it.

Most of the time, my first draft is bloated, over written, and confusing. This sentiment is often shared amongst writers; notably, Jack Epps, writer of Top Gun and professor at USC, mentions this feeling in his book Screenwriting is Rewriting. He mentions that first drafts often leave their writers feeling disastrous and equates the rewriting process to working at a construction site: the more you dig or change something, the more rubble that is left for you to deal with.

The daunting task, admittedly, is my least favorite, but it gives me a sense of hope that even the most talented writers feel the same way.

After a few days, weeks, or months (depending on how arduous the first draft was), I return to my work and attempt to look at it with unbiased eyes. I print a copy of whatever it was that I was working on so I can feel the hours spent in my fingertips and hopefully reignite my self-worth. Then, with a red pen, I ruthlessly edit away, marking typos, cringey lines of dialogue, or plot holes, because if I’m not my own biggest critic, I’d hate for someone else to be.

I try and let the writing settle. This is so when I come back, I can hopefully forget the parts that were supposed to be forgotten. If I, the writer, don’t remember writing them, then an audience member certainly won’t.

Writing is an everlasting process, only usually ending because of a deadline, so I try and cut the fat each time, hoping for a leaner, more digestible experience the next time around.